After a Florida bridge collapse tragedy, bridges were required to be built with protective “fenders” — but not until the 1990s.

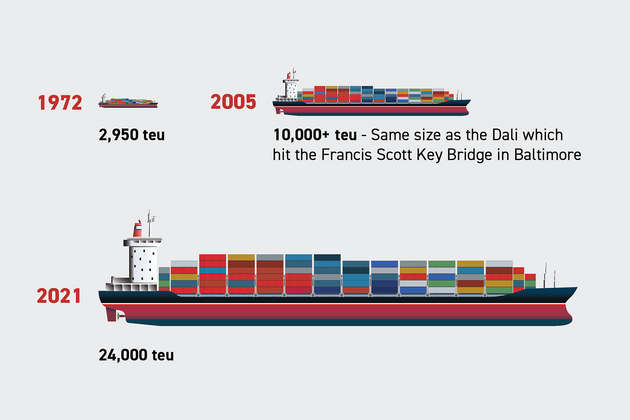

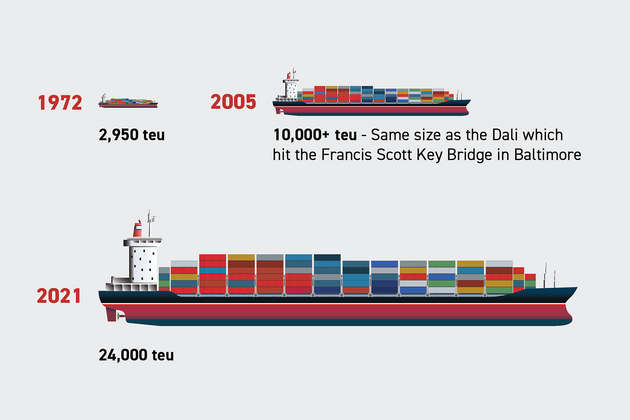

In the 1970s, when the Key Bridge was designed, ships were dramatically smaller and engineers would not have foreseen the behemoth container ships of today. | Claudine Hellmuth/POLITICO

The collapse of Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge on Tuesday after a collision with a massive container ship could have been mitigated with simple “fenders” that have been standard issue on new bridges since the 1990s.

Today these fenders are standard to be installed around supporting beams for new bridges to help blunt potential impact from cargo ships. They help combat the ever-increasing size of ships just like the thousand-foot-long Dali, which sent the bridge into the Patapsco River.

“Had [the Key Bridge] been designed for the criteria that were developed after the 1990s, I think it would have survived this event,” said Sherif El-Tawil, professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Michigan.

The Maryland Department of Transportation did not respond to multiple requests for comment about its bridge design standards, or whether the bridge was ever considered for fender retrofits.

In the 1970s, when the Key Bridge was designed, ships were dramatically smaller and engineers would not have foreseen the behemoth container ships of today. The largest ship in the world at that time was about a quarter of the size of the Dali, which is the length of a skyscraper. The average ship in 2024 is six times bigger than those of the late 1970s.

Even if fenders couldn’t completely stop the ship, they could have mitigated the scale of the disaster, said Sameh Badie, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at George Washington University.

“If we have a fender around the pier or a man-made island — which is going to at least reduce the impact force on the pier, even if the ship reaches the pier — it’s going to be a much better situation compared to what we have seen,” Badie said.

In 1977, when the Key Bridge in Baltimore opened, fenders existed, but were not yet standard. But three years later, the Sunshine Skyway Bridge across the Tampa Bay collapsed after a freighter hit a support pier during a sudden storm, killing 35 people.

Florida attorney Steve Yerrid of the Yerrid Law Firm successfully defended the captain of that freighter.

“If you look at the Baltimore bridge pictures, you’ll see the piers are unprotected,” Yerrid said in an interview. “That occurred in 1980, our horrific accident. So what I’m saying is, they didn’t learn. And for 44 years — I’m not saying they should have rebuilt their whole bridge, but they certainly should have taken safety measures.”

The bridge collapse in Florida was a “wake-up call for the entire maritime industry,” Yerrid said.

And in 1994, the group that sets the standards for road and bridge construction, the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, issued new regulations requiring devices like fenders wherever bridges are not “designed to resist vessel collision forces.”

The Key Bridge, built years before the new AASHTO guidelines, “did not benefit from that type of analysis,” said Sherif El-Tawil, the civil engineering professor.

Some states have begun to retrofit old bridges with these fenders.

The Delaware River and Bay Authority, for instance, is currently spending $95 million to install 80-foot diameter steel structures around each of the bridge’s two tower structures, augmenting existing protective measures..

“They’re not inconsequential,” said Public Information Officer James Salmon of the Delaware River and Bay Authority. “They’re a mammoth project.”

It’s unclear whether the Maryland Department of Transportation ever considered installing them for the Key Bridge. MDOT did not answer requests for comment for this article.

Catherine Sheridan, bridges and tunnels president for New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority, said in a statement that its bridges are equipped with “a wide range of safety technology, including ship collision protections.”

She noted that the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge, where the largest ship traffic passes, is a “special case in that it has a robust rip rap system (rock island around the tower bases) which would cause a ship to run aground before it could do significant damage to the bridge.”

AASHTO Executive Director Jim Tymon said he’s skeptical that better protection could have prevented Tuesday’s tragedy, noting the impact of the Dali was like “an aircraft carrier hitting that bridge.”

“We’ve got to see what the NTSB recommends before we jump to conclusions on what could have happened or what should have happened,” Tymon said. “Because it’s possible they come back and say, even with a different approach for protecting those bridge piers, they likely still would have sustained a strike and that bridge still would have come down.”

Source: Politico